Internment Camp Survivor Views Prejudice, Racism and Civil Rights Through a Seven-Decade Lens

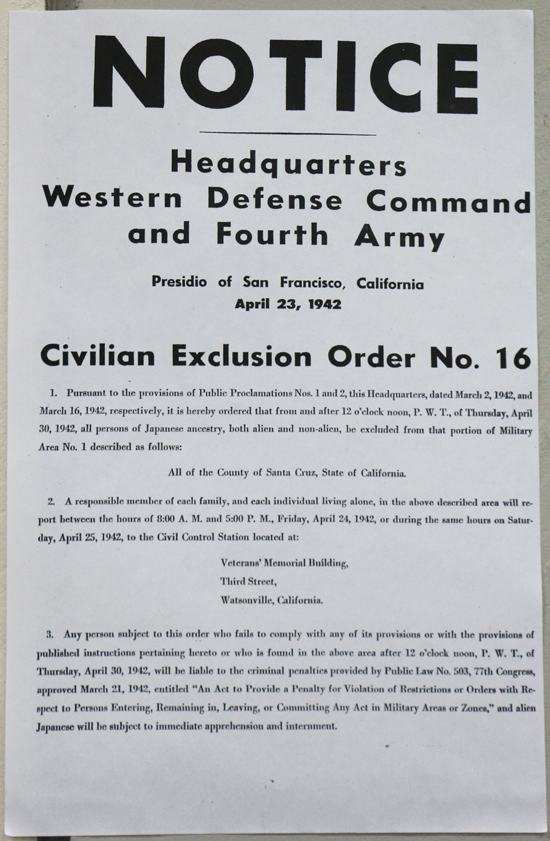

by Jan Janes on Dec 8, 2017First grader Mas Hashimoto was uprooted from his Watsonville home, along with his family, as authorities in California enforced Civilian Exclusion Order No. 16.

Hashimoto, now retired, spoke at Gavilan College about the Japanese internment, civil rights and racism. His presentation was one of several offered through A Closer Look, which examines issues of equity. Series topics held in cities throughout the college district also included gender and sexuality, the Holocaust and US/Russian relations. The program is funded by a Title V Civic Engagement Grant.

"Racism created the conditions of the executive order," said Hashimoto, referring to Executive Order 9066 issued by then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorizing incarceration of Japanese Americans, German Americans and Italian Americans.

"Nobody should go to prison because of the way they look."

Offering a different perspective, Hashimoto read the Japanese-American Creed penned

in May 1941 by Mike Masaoka, seven months before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

"I am proud that I am an American citizen of Japanese ancestry, for my very background makes me appreciate more fully the wonderful advantage of this nation," it begins.

Hashimoto and his family, along with other Watsonville internees, lived temporarily in a makeshift prison where the rodeo was held. People were housed in horse stalls. For months they dealt with the stench of manure and urine. Schoolteachers who came to teach the youth had car tires slashed and windshields smashed.

Transporting 500 people at a time, it took authorities more than a week to move everyone to two Indian reservations in Arizona, where Hashimoto and his family lived for three years.

"You could take only what you could carry. And bedding, no mattresses."

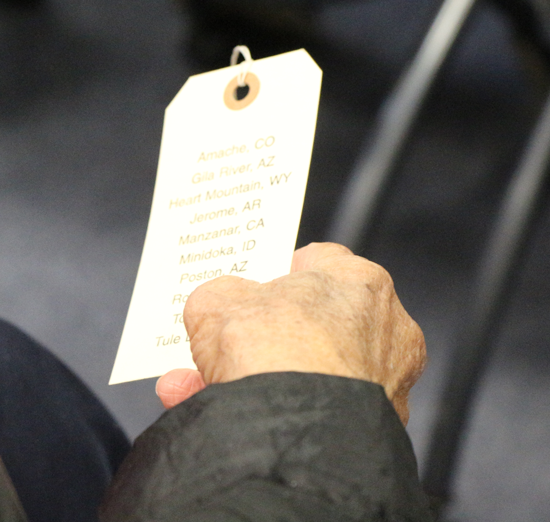

Everyone was labeled with an official tag. People who objected were imprisoned.

Even an American citizen who served in WWI had his citizenship revoked.

The Hashimotos boarded up but did not sell their house. Instead, they gave it to a trusted friend, along with their dog. A few months later, the friend sent the dog via bus to the internment camp. Mas Hashimoto had the only dog among 18,000 people.

"Dogs are color blind," he said. "I wish people were color blind."

At age 82, Hashimoto reflected on the decades of his career as student, farm worker, soldier and teacher.

He attended Watsonville schools during the school year. Starting at age ten, he worked in the fields harvesting strawberries and raspberries. "The hardest job, thinning lettuce," he said. Bent over, using a short-handled hoe, workers take out two and leave one.

"Do that, for 11 hours, for maybe five cents an hour," he said. He expressed gratitude for the work, because it provided money for his college education. He praised Cesar Chavez, who worked with the California Legislature to outlaw short-handled hoes.

"Summer vacation wasn't a vacation," Hashimoto said. "School was the vacation."

After graduating college and earning his teaching credential, Hashimoto was drafted into the Army during the 1950s. He worked in the chemical section where everyone had top secret clearance for nuclear, chemical and biological weapons. Completing a two year stint, he returned to Watsonville and taught high school history for 36 years.

He has examined racism and discrimination, from others and his own.

According to Hashimoto, service clubs, the McClatchy newspapers, Daughters of the American Revolution, Sons of the Golden West, even former California Governor Earl Warren all discriminated against Japanese Americans. Teachers were racist in how they graded.

"Some never gave Japanese American students more than a C, so they couldn't qualify for scholarships," he said.

Hashimoto used vacations during and after college to travel to the South, Canada, New Mexico and Texas.

Traveling in Mississippi, a friend chose to ride the bus a short distance. Watchful, Hashimoto followed in the car after his friend boarded the bus.

"My friend got on after whites, then black people got on after my Japanese American friend. The first three people boarding after my friend were wearing US military service uniforms."

Even when faced with personal examples of racism, Hashimoto could still ask of himself, "What did I know about black people?" At Watsonville High School, there was only one black student.

"If all you saw were Hollywood movies, you were brainwashed," he said. "In Gone with the Wind, blacks were portrayed as servant pets. In other movies, Latinos were portrayed as banditos, Asians as gangsters. Native Americans? The only good Indian was a dead Indian. In fights, the white guy wins." He loves local film festivals because they tell the stories of real people.

"Can you draw an American?" he asked the audience.

"If you don't know what an American looks like, draw me. My father was Japanese, my mother was Japanese. I am an American."

Mas Hashimoto, born in 1935, the depths of the Depression. People didn't know where their next meal was coming from. He went to prison at age six, along with his family.

Note the wording on the posters in item 1: Alien and non-alien.

The internment was unfair but legal. No charges, no attorney, no trial. The 1940 Census had recently concluded, so the government knew where everybody was. A majority of those forced into the camps were children, young people, American citizens.

"They didn't want to, couldn't write US citizen, so they wrote those words 'non-alien' instead," said Hashimoto.

"There's only one race, the human race."